Hi all. After spending over 20 years illustrating Australian birds for identification (Handbook of Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic Birds, Australian Bird Guide) I am now trying to find my way back to painting birds in their habitats and relying more on field sketching as well as photo references. My background is as a field biologist and I'm largely self-taught as an artist, though I was lucky to have W. T (Bill) Cooper as a mentor.

I'm interested to see how many Birdforum artists still use field sketching in their practice even in these days of digital photography; like most illustrators i use photo references a lot but still value that special connection that comes with seeing your subject in the field. If you are a practicing bird artist I'd be interested to hear how you work.

To get the ball rolling I've attached some of my artwork and welcome any feedback:

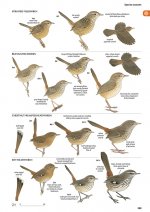

first is a plate from the recent Australian Bird Guide (Fieldwrens and Heathwrens)

next is an old field sketch of a Scarlet-rumped Trogon, recently worked up in watercolour with access to photo references

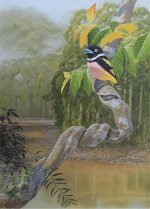

last is a picture of a bird in its habitat, a Back and yellow Broadbill I saw in Sabah, again based on field sketches and photo references

Cheers, Peter

I'm interested to see how many Birdforum artists still use field sketching in their practice even in these days of digital photography; like most illustrators i use photo references a lot but still value that special connection that comes with seeing your subject in the field. If you are a practicing bird artist I'd be interested to hear how you work.

To get the ball rolling I've attached some of my artwork and welcome any feedback:

first is a plate from the recent Australian Bird Guide (Fieldwrens and Heathwrens)

next is an old field sketch of a Scarlet-rumped Trogon, recently worked up in watercolour with access to photo references

last is a picture of a bird in its habitat, a Back and yellow Broadbill I saw in Sabah, again based on field sketches and photo references

Cheers, Peter