As a new birder, picking up an identification guide with 642 British birds including all the rarities is pretty daunting. Especially when you consider all the different plumages for each species and then of course you want to try and learn the songs/calls as well... you start to do the maths and think "I've somehow got to learn 1500 'visuals' and God knows how many sounds". So far I have just been looking through the guide in no particular order and doing most of the learning while I'm actually out there birdwatching (which I think is the best way because you won't forget it so easily after standing underneath a tree for half an hour, neck aching from staring up, freezing hands trying to match the tiny hyperactive bird with a still image in the field guide 🤣). But I wanted a way that I could learn in a more organised way as well as making it less daunting.

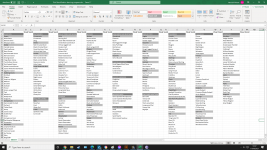

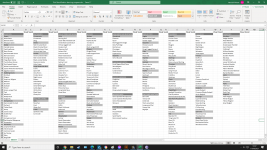

So I have made a spreadsheet listing all the commonly seen species in Britain, organised into their families/groups with two checkboxes next to each that I can mark when I feel I have learnt the visuals and sounds to a level that I would feel confident successfully identifying them out in the field. This way, each day or week or month I can take a species or group of birds and focus on studying just them - much more manageable

.

Below is the spreadsheet for if anyone else wants to make something similar:

View attachment 1379015

Knowing what I know now, there are quite a few things I would do differently in order to speed up the learning process, but one of the things I think I had right was not spending time learning the calls. When you have other things going in your life, as just about everyone does, time is limited; and learning how to use a camera, being out watching birds and taking pictures, learning how to photo edit and then actually photo editing are all time consuming activities. So for me, I sacrificed being sat at home learning calls in order to spend more time out with my camera and watching birds.

In my short space of time watching birds, 'say around a year, I could now instantly recognise the sound of a long tailed tit, a blue tit, a goldfinch, a wheatear, a blackcap, a marsh tit, a grasshopper warbler, a willow warbler, a pied flycatcher, a nuthatch, a song thrush, a mistle thrush, a goldcrest, a skylark, a meadow pipit and pretty much every other bird I have seen. The only one I would not recognise is a greenfinch and that's because every time I have seen them they've been tucked away in trees and there have been other birds around them and so I've never been clear on which is the greenfinch, and since I've gotten better with the calls I haven't seen a greenfinch to be able to nail it down by process of elimination.

It helps that I have a good memory, but if you're interested, which clearly you are; you will find that you very quickly get used to the habits and sounds of birds due to watching them through your binoculars and camera trying to get a picture. I'm not so sure you really need to learn the calls unless you're looking for specific birds. In the event a bird turns up that I haven't heard before, I'll know immediately that this is a new bird and then by waiting and watching it'll be etched into my memory which bird it is and the sound it makes when it comes into view.

Perhaps it's because I'm an accountant by trade and I spend my working days with spreadsheets and putting numbers in boxes that I crave not being restricted by tools designed as control mechanisms in my free time.

Given time limitations, I would learn the basics of the camera, decide upon which settings are for you, learn the basics of photo editing, spend as much time watching birds as possible, learn how to keep a camera steady ('takes practice and effort), learn how to get close to birds, and most of all enjoy it. By doing all of that, anyone with a decent memory will know which birds they've seen and what sounds they make without needing to log them.

I suppose these boards are for honest discussions, and so although I know the following is going to sound critical I'll give my view anyway: making lists and trying to control the situation through spreadsheets seems to me to be defeating the purpose of being among nature and in the event you have a camera then it's an attempt to turn what is essentially a creative pursuit into a logical one.

I do appreciate that you may have no plans to buy a camera and so you have a bit more time, but I would still go for being out as much as possible with my binoculars rather than being sat at home compiling lists and spreadsheets and you may be surprised at how much you learn in a short space of time through experience. If your memory fails you and you can't decipher which birds make which sounds, then lists and spreadsheets may be helpful but it would be a begrudging last resort for me.

Edited to add: long story short, if your goal is to enjoy watching birds and learn about them in the process, your better bet could well be to maximise your time out with your binoculars and place faith in your memory.

.

.