Fred Ruhe

Well-known member

Daniel T. Ksepka, Daniel J. Field, Tracy A. Heath, Walker Patt, Daniel B. Thomas, Simone Giovanardi & Alan J. D., Tennyson, 2023

Largest-known fossil penguin provides insight into the early evolution of sphenisciform body size and flipper anatomy

Journal of Paleontology: 1–20.

doi:10.1017/jpa.2022.88

Abstract: Largest-known fossil penguin provides insight into the early evolution of sphenisciform body size and flipper anatomy | Journal of Paleontology | Cambridge Core

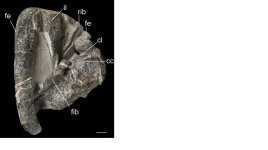

Recent fossil discoveries from New Zealand have revealed a remarkably diverse assemblage of Paleocene stem group penguins. Here, we add to this growing record by describing nine new penguin specimens from the late Paleocene (upper Teurian local stage; 55.5–59.5 Ma) Moeraki Formation of the South Island, New Zealand. The largest specimen is assigned to a new species, Kumimanu fordycei n. sp., which may have been the largest penguin ever to have lived. Allometric regressions based on humerus length and humerus proximal width of extant penguins yield mean estimates of a live body mass in the range of 148.0 kg (95% CI: 132.5 kg–165.3 kg) and 159.7 kg (95% CI: 142.6 kg–178.8 kg), respectively, for Kumimanu fordycei. A second new species, Petradyptes stonehousei n. gen. n. sp., is represented by five specimens and was slightly larger than the extant emperor penguin Aptenodytes forsteri. Two small humeri represent an additional smaller unnamed penguin species. Parsimony and Bayesian phylogenetic analyses recover Kumimanu and Petradyptes crownward of the early Paleocene mainland NZ taxa Waimanu and Muriwaimanu, but stemward of the Chatham Island taxon Kupoupou. These analyses differ, however, in the placement of these two taxa relative to Sequiwaimanu, Crossvallia, and Kaiika. The massive size and placement of Kumimanu fordycei close to the root of the penguin tree provide additional support for a scenario in which penguins reached the upper limit of sphenisciform body size very early in their evolutionary history, while still retaining numerous plesiomorphic features of the flipper.

Enjoy,

Fred

Largest-known fossil penguin provides insight into the early evolution of sphenisciform body size and flipper anatomy

Journal of Paleontology: 1–20.

doi:10.1017/jpa.2022.88

Abstract: Largest-known fossil penguin provides insight into the early evolution of sphenisciform body size and flipper anatomy | Journal of Paleontology | Cambridge Core

Recent fossil discoveries from New Zealand have revealed a remarkably diverse assemblage of Paleocene stem group penguins. Here, we add to this growing record by describing nine new penguin specimens from the late Paleocene (upper Teurian local stage; 55.5–59.5 Ma) Moeraki Formation of the South Island, New Zealand. The largest specimen is assigned to a new species, Kumimanu fordycei n. sp., which may have been the largest penguin ever to have lived. Allometric regressions based on humerus length and humerus proximal width of extant penguins yield mean estimates of a live body mass in the range of 148.0 kg (95% CI: 132.5 kg–165.3 kg) and 159.7 kg (95% CI: 142.6 kg–178.8 kg), respectively, for Kumimanu fordycei. A second new species, Petradyptes stonehousei n. gen. n. sp., is represented by five specimens and was slightly larger than the extant emperor penguin Aptenodytes forsteri. Two small humeri represent an additional smaller unnamed penguin species. Parsimony and Bayesian phylogenetic analyses recover Kumimanu and Petradyptes crownward of the early Paleocene mainland NZ taxa Waimanu and Muriwaimanu, but stemward of the Chatham Island taxon Kupoupou. These analyses differ, however, in the placement of these two taxa relative to Sequiwaimanu, Crossvallia, and Kaiika. The massive size and placement of Kumimanu fordycei close to the root of the penguin tree provide additional support for a scenario in which penguins reached the upper limit of sphenisciform body size very early in their evolutionary history, while still retaining numerous plesiomorphic features of the flipper.

Enjoy,

Fred