l_raty

laurent raty

And did you find any supplemental file ?Oh god...searching for the supplemental files for the Černý and Natale (2021) resulted in me discovering that Pterosaur Heresies has also found the paper. Lord have mercy on us all...

And did you find any supplemental file ?Oh god...searching for the supplemental files for the Černý and Natale (2021) resulted in me discovering that Pterosaur Heresies has also found the paper. Lord have mercy on us all...

Here 😁And did you find any supplemental file ?

No, this is not what I was looking for. (It's interesting, though, so thanks for it nevertheless.) I'm after this:Here 😁

All GenBank accession numbers, alignments, tree files, configuration files, and R scripts are available from the Dryad Digital Repository: http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.nnnnnnnnn.

Not sure I feel comfortable splitting apart Calidris. While in theory I don't mind cryptic genera, to me the degree of morphological similarity makes me question the merit of finely splitting apart the genus as currently recognized. I could be convinced, but given this seems to be going against the tide of prevailing thought by other taxonomic bodies I will wait and see.

Can the maintenance of a single genus which includes Ruff, Surfbird, Curlew Sandpiper, Buff-breasted Sandpiper and Spoon-billed Sandpiper, amongst other disparate forms, really be justified by arguments of morphological similarity?

I don't disagree with what you are saying - if the genetics are correct, there's some serious morphological conservatism going on in this group, though some of the less convincing details may be refined with more studies. But, for me, a broad Calidris is too heterogeneous and something as morphologically and behaviourally idiosyncratic as Ruff should not have been taken out of a monospecific genus - especially when this is supported by divergence time estimates (Černý and Natale (2021) have it as an isolated lineage for 19 million years). And if you start with a monospecific Philomachus, then, based on current understanding, the remainder must be carved up something akin to the genera I outlined above - though other genera could also be recognised (e. g. Micropalama, Leimonites, Crocethia).On the other hand, breaking up Calidris results in some arrangements that are hard to fathom. At least as a field birder, it's hard to believe that Least Sandpiper and Long-toed Stint are in separate genera, same for Semipalmated Sandpiper and Red-necked Stint. Sharp-tailed Sandpiper being sister to Broad-billed, and in a separate genus from Pectoral, is another suprising result.

Plus you'd have to change the title of what to me remains the greatest field identification article ever published: https://sora.unm.edu/sites/default/files/journals/nab/v038n05/p00853-p00876.pdf

The other bit of clear nonsense in this group is the current positioning of forbesi to tricollaris.

And I hope that you will not forget to have a look on the apparently overlumped genus Vanellus which has been neglected much too long.The take home message is that essentially we need to burnt it all to the ground and start again. The other bit of clear nonsense in this group is the current positioning of forbesi to tricollaris.

My research is currently focused on shorebirds, with a particular focus on some Charadrius species. I have been pushing for a new look at this with some of my colleagues and hopefully we can do a resampling drive!

I can reveal that there should be one or two papers of interest to this subforum from Charadrius species this year. Watch this space!

This is the same paper that was discussed around New Years, correct? And not a new article?

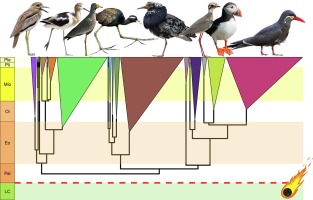

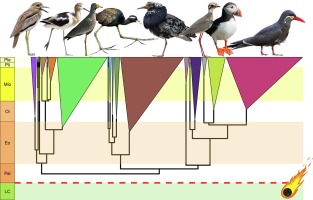

Comprehensive taxon sampling and vetted fossils help clarify the time tree of shorebirds (Aves, Charadriiformes)

Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) are a globally distributed clade of modern birds and, due to their ecological and morphological disparity, a frequent sub…www.sciencedirect.com

C'est the same ouiThis is the same paper that was discussed around New Years, correct? And not a new article?