foresttwitcher

Virtually unknown member

In England an 'overhead wire' could refer to either telephone or electricity lines, the latter both on poles or pylons.

"As soon as the hawk-hunter steps from his door he knows the way of the wind, he feels the weight of the air. Far within himself he seems to see the hawk’s day growing steadily towards the light of their first encounter. Time and the weather hold both hawk and watcher between their turning poles. When the hawk is found, the hunter can look lovingly back at all the tedium and misery of searching and waiting that went before."

Do you think "turning poles" is a reference to the poles and gates in slalom skiing?

"Ringing recoveries suggest that immigrants to the east coast of England have come from Scandinavia. No British-ringed peregrines have been recovering in south-east England."

Just curious, how were bird rings recovered, just technically, in the 1960s? The latter "recovering" means the peregrines were taking rest, right?

"They may in fact be returning to places where their ancestors nested. Peregrines that now nest in the tundra conditions of Lapland and the Norwegian mountains may be the descendants of those birds that once nested in the tundra regions of the lower Thames. Peregrines have always lived as near the permafrost limit as possible."

Does Baker mean that young peregrines choose the types of places, not exact locations, where their ancestors dwelled? Because in the second sentence here he speaks about ancestors and descendants living in areas far away from one other.

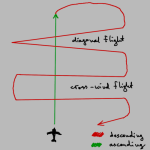

"These hunting lines may run from estuary to reservoir to valley, and from valley to estuary; or they may follow the lines of flight from roosting places to bathing places. The territory is also effectively quartered by long up-wind flights, followed by diagonal down and cross wind gliding that finishes a mile or two away from the original starting point. Hunting on sunny days is done chiefly by soaring and circling down wind, and is based on a similar diagonal quartering of the ground."

Does Baker mean something in the way of what I drew in the picture? Does "quartering" mean "patrolling" here, more or less?

View attachment 1557680

No, not really.I think you're confused by his use of "up" and "down".

The same is true when "soaring and circling downwind" with the added likelihood that the bird can find some thermals within which to circle

The difference I see between C2 and S2 is that S2 involves circling. I think Baker is using "soaring" to mean flying in circles, possibly with gain of height. Whereas I think he uses "gliding" for flying in a straight line without flapping the wings, and plain "flight" for flying that involves flapping.

(C2) diagonal down and cross wind gliding

Time and the weather hold both hawk and watcher between their turning poles.

Do you think "turning poles" is a reference to the poles and gates in slalom skiing?

"Ringing recoveries suggest that immigrants to the east coast of England have come from Scandinavia. No British-ringed peregrines have been recovering in south-east England."

Just curious, how were bird rings recovered, just technically, in the 1960s? The latter "recovering" means the peregrines were taking rest, right?

"They may in fact be returning to places where their ancestors nested. Peregrines that now nest in the tundra conditions of Lapland and the Norwegian mountains may be the descendants of those birds that once nested in the tundra regions of the lower Thames. Peregrines have always lived as near the permafrost limit as possible."

Basically yes. His meaning is that as the glaciers receded, peregrines that nested in the tundra gradually moved north.Does Baker mean that young peregrines choose the types of places, not exact locations, where their ancestors dwelled? Because in the second sentence here he speaks about ancestors and descendants living in areas far away from one other.

Baker: "The hunting hawk uses every advantage he can. Height is the obvious one. He may stoop (stoop is another word for swoop) at prey from any height between three feet and three thousand. Ideally, prey is taken by surprise"There is a difference between swooping and stooping.

Baker: "The hunting hawk uses every advantage he can. Height is the obvious one. He may stoop (stoop is another word for swoop) at prey from any height between three feet and three thousand. Ideally, prey is taken by surprise"

It seems that Baker writes "swooping" and "stooping" now as synonyms, now as different kinds of flight.

Yes, like you said, this sentence, "stoop is another word for swoop", was at the beginning of the book and was the first time the word "swoop" was used. I've gone through these two words again and it seems that mostly Baker uses them as direct synonyms, but occasionally "swooping" means just what you wrote, "To swoop on the other hand is more general sort of term that describes a swift downward movement". Also, "swooping" is sometimes used to describe the flight of non-raptors, such as ducks and pigeons. And, Baker sometimes writes "to swoop up" (e. g., to a perching position), which clearly has nothing to do with attacking.If Baker states that stoop and swoop are the same, then it should be taken that way, certainly in the context of his book. There is a difference, though, and not just to me

"The peregrine swoops down towards his prey. As he descends, his legs are extended forward till the feet are underneath his breast. The toes are clenched, with the long hind toe projecting below the three front ones, which are bent up out of the way. He passes close to the bird, almost touching it with his body...

It has to mean he didn't see a peregrine until 6.00pm that day.

I have some friendly questions for you ... which parts of the book have you enjoyed the most so far?

What are your thoughts on Baker as a writer?

How do you think Baker's style of writing translates into Russian? Do you think your translation gives the same feeling when read in Russian as you feel when reading the original text in English?

Most of all, do you think differently about peregrines (and indeed birds in general) after having read a book that focuses on them so much?

I've had the odd glass of Bordeaux that had gone that colour S@nartreb That is probably what Baker meant, although these feathers are neither a rim, nor wine-colored.