Migration

The need for migration

Birds migrate for two main reasons

- To move from areas of decreasing food or water supply to areas of increasing or high availability of food or water.

- To find suitable breeding sites.

The two are often linked, because areas of increased food supply are often in remote areas such as the Arctic Circle where daylight increases in the Summer months to peak at 24 hours a day, ideal to support vast numbers of insects and plants. These remote areas are not very accessible or desirable for human habitation and so provide good natural nesting sites.

Birds are quite resilient to cold and although migrating to avoid it is a factor, it is mainly the decreasing availability of food that drives the migration.

Migration triggers

Different species and even different populations within a species often have different triggers. This is not yet fully understood, but several factors are thought to trigger migration.

- Biological triggers which include hormonal changes and genetic influences which show as inborn ability.

- Changes in day lengths.

- Changes in temperature, which is strongly linked to:

- Weather conditions.

- Availability of food or water.

As changes in day length, temperature and food availability takes place, some species, particularly long distance migrants, have a biological pre-migratory response. Many long distance migrants moult before migration to ensure maximum efficiency of their plumage, as worn and abraided feathers lose efficiency over time. Another part of the preparation is a process known as hyperphagia It enables them to overeat, thus gaining the fat reserves (hyperlipogenesis) that are needed to survive the journey. (example needed) Some species only lay down enough fat to reach the next staging post, where they fatten up for the onward journey. Others lay down enough reserves for a non-stop flight. (examples needed) It is a critical process, because too much weight takes more energy to get there and too little means starvation on route.

Types of migration

Migration may be considered not only in terms of length of distance travelled. Some species migrate between the high Arctic and Antarctic. Others travel much shorter distances between their breeding and wintering quarters, but also the methods used to achieve this. These include:

Loop migration

Birds use a different route for the Spring and Autumn migration. These are influenced by several factors.

Geography and weather conditions: Mountain ranges create natural barriers that channel birds naturally along their length, but if the weather conditions are right, certain families of raptors can utilise updrafts and thermals to save energy when travelling in one or both directions. (examples needed) On the opposite leg these conditions aren't there and they use a different route.

Food availability: some bird species, such as Eleonora's Falcon time their migration to follow swarms of migrating insects . These food sources are not available on return migration, so birds use other factors to decide the route used.

Altitude Migration

Where birds move from one altitude to a lower one and back. Usually, this takes place before winter when food becomes hard to find at higher altitudes, forcing them to move to lower levels. The birds then return when the snows melt. It is normally a mid range movement from one geographical area to another, but it can also occur over short distances when a birds moves down a valley to escape the worst of the snow.

Leapfrog Migration

Some species including Canada Goose move to the equivalent latitude in the Southern hemisphere on their winter migration, thus leapfrogging shorter range migrants who travel a shorter distance to the equivalent in latitude in the opposite hemisphere.

Drift Migration

High winds, mist or fog may cause migrating birds to be blown off course or lose orientation and fly off course. This is more prevalent during the Autumn migration with juveniles birds undergoing their first migration. (examples needed)

Reverse Migration

Some species of passerines have a gene that causes the first migration in juveniles. Yellow-breasted Bunting (further examples needed) If the gene responsible is faulty, this may cause the birds to fly in completely the wrong direction by 180 degrees. (insert map. example Reverse migration (birds) - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia)

Delayed migration

The effects of drought can cause delays in the Spring migration from birds leaving their wintering grounds in Africa. Global warming has caused delays in the Autumn migration for birds leaving their breeding grounds in the high Arctic.

Prolonged stopovers

Extremely cold weather in Europe causes a prolonged delay in the Spring migration. The birds have to wait until the snow and ice retreats before they can continue with their migration. Loss of suitably large stop over areas cause food shortages. Birds are forced to turn around and fly back to suitable sites.

Birds have several methods by which they can navigate their way across the globe during migration.

The sun's azimuth

It is not the sun's height in the sky that some species use to navigate, but rather it's azimuth, the angle of the sun on the horizon. It has also been discovered that orientation using the sun is learnt early in life imprinting the data in the bird's memory. The circadian rhythm, the bird's inner clock if you like, has also to be synchronised with this

Light polarisation

Light is polarised when daylight hits particles in the atmosphere and line up in a north/south direction particularly as the sun is setting. This alignment is thought to be seen by birds even when the sun is obscured by cloud.

Magnetic sense

The magnetic field of the Earth has three components: direction, angle and intensity. The direction of this field points to the magnetic North Pole. The angle is the angle between the magnetic field lines and the surface of the Earth The magnetic field variation around the globe can be used as a map, once the variations are learned by the bird. The intensity of the magnetic field can be used in a similar way to map migration routes.

Scientists believe that there are up to three ways that this works.

- Small iron oxide (magnetite) crystals could provide a compass.

- The magnetic field is seen by the bird’s eye.

- The bird's inner ear, it's sense of balance, enables it to "feel" the magnetic field.

Scientists currently think that birds have a compass in their eyes and a magnetic mapping device in their upper mandible.

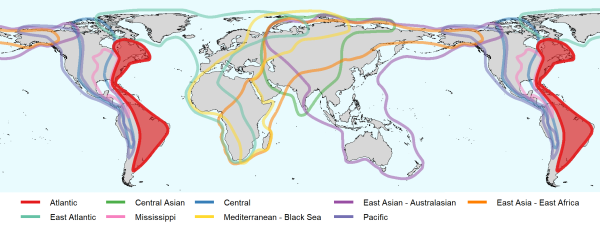

Migration Routes

The main corridors that birds use are known as flyways. Their boundaries are not fixed and different authors recognise slightly different numbers of routes. They also vary somewhat according to the types of birds that are migrating: passerines tend to be more catholic in their choices resulting in them following fewer distinct paths. For example, in North America authorities often distinguish 4 flyways (Pacific, Central, Mississippi, Atlantic) based on movements of raptors and waterfowl. However, these might be better treated as only 3 for passerines [19],[20].

World Flyways

Birdlife International suggests there are 8 major routes around the world. Other authors may divide these up in slightly different ways. Here we discuss nine global Flyways.

American Flyways

Birds follow three or four main paths when they migrate through the Americas. The four routes we discuss below are based on those suggested by studies of waterbird and raptor migration. Passerines may follow three major paths.

Atlantic Flyway

Starting at the Arctic's Baffin Island in the north this flyway stretches ever south to the Caribbean and spans more than 3,000 miles or 4,828 km and includes the USA states of Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Vermont, Virginia, and West Virginia. In Canada, it includes the provinces of Newfoundland, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Ontario, Prince Edward Island, Quebec and the territory of Nunavut. This flyway also reaches Greenland. It is the eastern most flyway in North America. About 500 species of birds use this flyway.

Birdlife combines the Atlantic with part of the Mississippi Flyway in its "Atlantic Americas" Flyway. This may be appropriate if the focus is passerines or perhaps all bird groups.

Mississippi Flyway

Over 325 bird species use the Mississippi Flyway, for their round-trip each year from their breeding grounds in Canada and the northern USA to their wintering grounds along the Gulf of Mexico and in Central and South America. It is a corridor comprising the states of Alabama, Arkansas, Indiana, Illinois, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Ohio, Tennessee, Wisconsin and the Canadian provinces of Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Ontario.

Central Flyway

Starts in the Arctic, moves south through the Great Plains of Canada and the United States of America (USA), the western seaboard of the Gulf of Mexico and southwards to Patagonia. The main endpoints of the flyway are in central Canada and the Gulf coast of Mexico, but some species use it to migrate from the high Arctic to Patagonia. (examples needed). The route narrows along the Platte and Missouri rivers of central and eastern Nebraska, which gives a high species count there.

The following states lie within the flyway: Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, New Mexico, Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, [[Nebraska], South Dakota, and North Dakota. In Canada the flyway comprises the provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan and the Northwest Territories

Pacific Flyway

Runs from the Siberian tundra through Alaska in the north down to Tierra del Fuego in the south along the eastern Pacific coastline. Over 300 species are known to use this flyway, including millions of wildfowl, passerines and waders. Stopover points along this route include

- Copper River Delta, Alaska. Here, up to 1.1 million waders pass though during the peak Spring migration (April 25 – May 15). Vast numbers of Western Sandpiper and Dunlin C. a. pacifica, the most numerous waders of the Pacific Coast, stop here before migrating to their breeding areas. The estuarine mudflats between the barrier islands and the shoreline provide their main source of nourishment in the Gulf of Alaska. Access to these has a major influence on their ability to reproduce further north and west in both Alaska and Siberia. The upland marshes are significant in value for other waders that reproduce there: Short-billed Dowitcher, Least Sandpiper, Greater Yellowlegs, Wilson's Snipe, Red-necked Phalarope, Spotted Sandpiper, Semipalmated Plover and to a lesser extent, Lesser Yellowlegs.

- Fraser River estuary, Canada. These coastal wetlands provide support for over 1.4 million waders including Western Sandpiper; 240,000 waterfowl including Snow Geese and about 4,000 raptors like Barn Owl, Bald Eagle and Peregrine Falcon. There are 262 bird species, (Jun 2021), in the Delta, 65% are migratory.

- Old Crow Flats, Yukon Territory. up to 300,000 birds nest in this region. They are joined in the post-breeding period by more birds arriving to moult, fatten up and prepare for migration.

- Stikine River Delta, Alaska. This provides food for up to three million migrating birds annually including 14,000 Snow Goose, over 10,000 Sandhill Cranes, up to 164,000 Western Sandpiper and nearly 2000 Bald and Golden Eagles.

- Upper Bay, Panama

- Humedales de Pacoa, Ecuador. Especially the area between Monteverde and San Pablo.

Alternative view of routes through the Americas

A) The approach we discuss here source? B) Birdlife International's flyways

© by THE_FERN

Birdlife International identifies three major migration routes through the Americas: the "Atlantic Americas", "Central Americas", and "Pacific Americas" Flyways. The broadly cover the same areas as the four routes we discuss above although details differ. The "Central Americas" route is roughly equivalent to the combination of the "Central" and "Mississippi" Flyways. Birdlife's flyways show that some other routes encompass parts of high latitude North America: the primarily Asian "East Asian - East Africa" and "East Asian - Australasian" Flyways extend to include parts of Alaska. Conversely, the "Pacific Americas" Flyway includes parts of north-eastern Siberia. In the east, the "East Atlantic" Flyway includes Baffin Island.

Austral migration

Austral migrants are species of birds that breed in the temperate areas of South America and move north into areas including the Pantanal the Amazon basin and more rarely, as far as the Caribbean for the Austral Winter and return in the Spring. They include many species of ducks and geese and passerines such as the largest group, the tyrant flycatchers.

Afro-palearctic Flyways

Birds migrating to Africa take one of three main routes.

East Atlantic Flyway

This route starts at various points in the high Arctic. These include Baffin Island, the Greenland coastline, Iceland and down through the North Sea to the Wadden Sea. Birds starting from Novaya Semlya in Siberia reach the Wadden Sea via the Baltic Sea. The Olonets Plains in Russia host over 500,000 Greater White-fronted Geese and more than 200,000 Bean Geese. Scandinavian birds make the crossing to Denmark at Falsterbo. It is the first major wintering and staging point for onward migration. Birds coming from Greenland also have stop overs in Shetland and along the coast of East Anglia on England's east coast before they cross the North Sea.

One the greatest hurdles for migratory birds to overcome is large bodies of water. The Straights of Gibraltar is the shortest way over the Mediterranean Sea that have to be crossed between the continents of Europe and Africa. They are crossed by 250,000 raptors per season. Following the West African coastline there are major stop overs or end points at the Banc d'Arguin National Park in Mauritania, where 2.25 million Waders overwinter. Next is the Djoudj wetland in Senegal, where 2 million Sand Martins find their wintering quarters. Further down the coast are the Arquipélago dos Bijagós mudflats in Guinea-Bissau which support over 500,000 waders. Little is understood about migration further south along central and Southern Africa.

Mediterranean - Black Sea Flyway

to be filled with text

East Asia - East Africa Flyway

to be filled with text

Asian Flyways

Central Asian Flyway

to be filled with text

East Asian - Australasian Flyway

to be filled with text

Trans-Pacific Flyway

The flyway goes from the Arctic ocean crossing the Pacific Ocean using several routes described later and on to destinations from between the Tasman Sea between Australia and New Zealand and French Polynesia. Breeding sites occur mainly on route including the Arctic and Sub-Arctic regions of Alaska, Canada and eastern Asia, the Aleutian Islands. Large numbers of remote Pacific islands are in this flyway including Midway Atoll, the Hawaiian Islands, the Northern Mariana Islands, Guam, Marshall Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Palmyra Atoll,Kiribati's Gilbert Islands, Phoenix Islands and Line islands, Solomon Islands, Tuvalu, Samoa, Tonga, Cook Islands, French Polynesia and New Zealand. The Pacific Islands National Wildlife Refuge (NWR) complex is a group of about 50 islands in the Line islands. National Wildlife Refuges along these routes include:

- Izembek Lagoon, Alaska. The peninsula lies between the Bering Sea and the Gulf of Alaska: migrants include: Black Brant Goose B. b. nigricans; 150-200,000, nearly all of the Pacific population of Black Brant use this site to moult, fatten up and prepare for the southern migration About 50,000 remain here for the winter. The number of overwintering geese is increasing with global warming. Taverner´s Cackling Goose B. h. taverneri, Emperor Goose; 70,000, over half of the world population migrate through Izembek. Steller's Eider; 23,000 birds moult, fatten up and prepare for their southern migration here.

- Midway Atoll, Pacific. Migatory species include Ruddy Turnstone, Wandering Tattler, Pacific Golden Plover, Bristle-thighed Curlew and Long-billed Dowitcher.

- Kealia Pond, Maui, Hawaii. The refuge is a wetland along Kealia Beach in Maalaea Bay in the south west of the island.

- James Campbell NWR, O'ahu. Between the heliport at Turtle Bay and Kahuku.

- Hanalei NWR, Kaua’i. Located south of Princeville on the northern shore. Migratory species include Bristle-thighed Curlew, Pacific Golden-Plover, Northern Shoveler, Northern Pintail and Snow Goose.

Pacific Island stopover and breeding sites include one or more of the following routes used by a number of long distance migrants, including the following species; Bar-tailed Godwit, Bristle-thighed Curlew, Wandering Tattler and Pacific Golden-Plover.

- Evidence suggests that there is a migration route for the Pacific Golden-Plover through Japan, Honshu, the Ogasawara Islands, Iwo Islands to the Northern Mariana Islands (NMI) -splitting to either Yap in the western Federated States of Micronesia and ending in either Palau. Or the NMI over the Marshall Islands, Gilbert and Phoenix Islands of Kiribati and on to French Polynesia. Palau also has migrating birds from south Asia and Australia.

- A second route, used by the Bar-tailed Godwit and Pacific Golden Plover, crosses from the Gulf of Alaska to the Yellow Sea between China and Korea, but further south across the open ocean than in the East Asia - Australasia Flyway discussed earlier.

- From the Yellow Sea, The Bar-tailed Godwit follows a third route that goes broadly via the Solomon Islands to Vanuatu, New Caledonia and ending at New Zealand where they overwinter.

- The fourth route goes from Alaska southwest over the Hawaiian Islands between approximately Lisianski Island and Necker Island on to the Marshall Islands, where the Bristle-thighed Curlew overwinters or goes northwest to Wake Island or southeast to the the Gilbert Island group of Kiribati. The Bar-tailed Godwit travels further to Vanatu where it joins the second route. There is also evidence that the Pacific Golden Plover uses this route.

- Route five is a route used by Bristle-thighed Curlew starts from Gulf of Alaska, goes southeast to approximately 50°N, 140°W, then almost due south to French Polynesia.

- The mudflats of the Suva Peninsular in Fiji has been noted as an Site of National Significance with the southern migration of species including: Wandering Tattler; 1% of the world's population, Short-tailed Shearwater, Cook's Petrel, Ruddy Turnstone, Pacific Golden Plover and Mottled Petrel listed.

Migration hazards

Predation

Human hunters pose a serious hazard to migratoory birds. Those channelled over the Mediterranean Islands of Malta and Cyprus, along the North African coastline and in the Sahel south of the Sahara are at risk from mist net traps. In the USA, hunting is having a major negative effect on populations during migration. Along the East Asian -Australasian Flyway illegal hunting is having an adverse affect to populations of migrating birds.

Man-made obstacles

Power lines and wind farms take a large toll of migrating birds along the flyways each migration period. In North America alone, power lines kill up to 64 million birds a year.

Another 7 million are thought to die in collisions with telecommunications towers.

Approximately 234,000 bird deaths a year are caused by wind turbines. These deaths are for all birds. Not just those on migration. However, the majority of these deaths are from migratory birds, especially song birds which migrate at night.

Most deaths occur during take off and landing where these turbines are next to stop-over sites.

Large buildings have caused large numbers of fatalities to migrating birds. In the USA up to one billion deaths occur anually. In one incident, 1000 birds were killed by a combination of weather conditions, heavy migration and bright lights on just one building in Chicago, Illinois in one night.

In 2021 Illinois passed the Bird Safe Buildings Act, which requires bird safety design to be incorporated for all new and renovated state-owned construction projects.

Road traffic collisions cause an estimated 89 million to 340 million bird deaths annually in the USA.

Desertification

An increase in desertification in the Sahel region south of the Sahara makes it more difficult for birds to find food on route. Recent climate change effects show increased periods of drought throughout many area of the world, including along migration flyways.

Change of farming methods

Increased use of and change in type of pesticides used have had a massive negative impact of insect population and intensification of farming methods have caused severe threats to migrating birds.

Accidental or deliberate introduction of invasive species

Islands in particular, have had huge negative effects by the introduction of species.

- Domestic cats Felis catus have aided in the extinction or near extinction to many island species. This may have a knock on effect for migrating birds.

- Rodents, especially rats, notably pacific rats Rattus exulans, ship rats R. rattus and brown rats R. norvegicus and mice either directly or indirectly have caused a reduction in both migratory and non-migratory bird species. Direct predation is usually on eggs or chicks. Indirect interaction is usually on the predation of plant species in direct competition to avian species.

- The decision to import, for example, the common brushtail possum, Trichosurus vulpecula to establish a fur trade in New Zealand has had serious consequences for natural ecosystems. Mainly folivorous, possums are also opportunistic omnivores. They eat all parts of plants including; leaves, fruit, buds, flowers and nectar. competing with endemic birds and reptiles. This significantly affects tree and plant growth. Possums have a greater impact on species such as rātā trees, genus Metrosideros or kamahi Pterophylla racemosa, in direct competition to avian species such as Tui, New Zealand Bellbird and New Zealand Kaka. The Chatham Bellbird is now extint. They also occupy tree cavities for nesting in direct competition birds such as Red-crowned Parakeet and Saddlebacks.

- Stoat Mustela erminea as well as the above mentioned possum, also predate bird eggs and chicks, including that of the Kea.

- Feral livestock, particularly pigs, cattle and goats have had a major impact on island biodiversity through habitat loss, nest damage or herbivory in direct competition to endemic species.

Habitat change at stop over sites

Reduction of and change of usage to stop-over sites also cause loss of life to migratory birds.

Effects of Global Warming

With global warming effects being felt in the Arctic Circle, birds, particularly geese are staying longer and even overwintering in greater numbers. Pressure is increasing on the vegation biomass as more geese are feeding on it, the growth period is changing at a slower rate. Migrating geese are increasingly at risk of failing to reach their breeding grounds in the high Arctic as competition for plant biomass becomes more critical.

Natural Barriers to Migration

Bodies of Water

Mediterranean, Gulf of Mexico

Desert

Crossing large areas of desert like the Sahara will require different strategies.

Direct Flight

This strategy is used where a bird flies non-stop over the whole desert.

Oasis to Oasis

This involves migrants flying at night and resting up during the day. Each leg is between oases where water and food are available.

Flight by night, stop-over by day

Using this method, a bird or flock of birds will fly straight across the desert at night. The birds will not eat and use up the reserves they have laid down premigration, or at previous stop-overs on route. The daylight will be used for resting and conserving energy. Sometimes birds will extend their night flight into the day if conditions, such as a good tail wind, allow.

Gradual movement using vegetated areas

The only routes across the Sahara using this method is by following the Nile river, or taking the coastal route along the west African coastline. The Nile is bordered with vegetation. Either swamp, or a narrow band of farmland. The coastline has as broader belt of sparse desert vegetation along it's route.

Migrating birds may use a combination of these methods. The second and third method are often combined where oases have dried up, or the distance between them is too far for one leg.

Mountain Ranges

Mountain ranges create natural barriers to migration that most species of migrating birds need to fly around. There are some species that have evolved that are able to cross these barriers.

Himalayas

The Bar-headed Goose migrates over this range. Northern Pintail carcasses have been found high in the Himalayas.

Ural Mountains

The Urals present a major obstacle for up to 2 billion birds heading south from the Russian Arctic that go on to use the Afro-Palearctic Flyway and returning in the Spring of the following year. Many are juveniles making the crossing without adult guidance. Some species migrate in different groups; these are defined by age and sex due to feather moult needs, or child rearing methods.

Conservation and International Conventions

The Convention on Wetlands (Ramsar), the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS), the International Migratory Bird Treaty Act (IMBTA) and other national and international agreements and conventions have been passed in an attempt to protect wildlife and the areas they utilise. The effectiveness of these conventions and treaties determine the success of conservation projects in the past, present and for the future.

Ramsar

Convention on Migratory Species

International Migratory Bird Treaty Act

Berne Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats

Convention on Nature Protection and Wildlife Preservation in the Western Hemisphere

Further Reading

- Alerstam, T. 1982. Bird Migration. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge

- Berthold, P. and S. B. Terrill. 1991. Recent Advances in Studies of Bird Migration. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics . 22: 357-78.

- Berthold, P. 1993. Bird Migration: A General Survey. Oxford University Press. Oxford, New York, and Tokyo.

- Gwinner, E., ed. 1990. Bird Migration Physiology and Ecophysiology . Springer-Verlag. New York, Berlin, and Heidelberg.

- Horton, Kyle G. et al. Phenology of avian migration has shifted at a continental scale. Nature Climate Change Vol 10 Jan 2020 63-68 https://www.nature.com/articles/s41558-019-0648-9

- Klaassen, Marcel et al. Ecophysiology of avian migration in the face of current global hazards. Royal Society London, Philosophical Transactions B Biol Sci. 2012 Jun 19; 367(1596): 1719–1732.

- The Evolution of Bird Migration Adapted from the Handbook of Bird Biology, Third Edition, April 11, 2017 https://www.allaboutbirds.org/news/the-evolution-of-bird-migration/

- William, T. C. and J. M. Williams. 1.Oct 1978. An Oceanic Mass Migration of Land Birds. Scientific American. 239(4): 166-176.

- https://chinadialogue.net/en/nature/how-has-the-ramsar-convention-shaped-chinas-wetland-protection/

References

Many thanks to all of our referenced sources.

- Beat about the Bush Trevor Carnaby Jacana Media ISBN 978-1-77009-241-9

- Bird Life International (2010) Spotlight on flyways. Presented as part of the BirdLife State of the world's birds website. Available from: http://www.birdlife.org/datazone

- Bird orientation: compensation for wind drift in migrating raptors is age dependent. Thorup et al, The Royal Society, Biology Letters

- CMS_Flyways_Reviews_Web.pdf

- Der Falke Journal für Vogelbeobachter Bird mgration - 23.2014.pdf

- Drift migration - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia, Kasper Thorup, Thomas Alerstam, Mikael Hake, Nils Kjellén (2003).

- Flyways.us

- Gilroy, James J.; Lees, Alexander C. (September 2003). "Vagrancy theories: are autumn vagrants really reverse migrants?" (PDF). British Birds 96: 427–438.

- Lehigh Earth Observatory

- Migration Hotspots Tim Harris Bloomsbury, ISBN: 9781408171172

- Migration in South America: an overview of the austral system Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 May 2010 R. Terry Chesser

- Peter Weaver's Birdwatcher's Dictionary Copyright © 1981 by Peter Weaver

- Rare birds in Britain and Ireland a photographic record. London: Collins. p. 192. ISBN 0002199769.

- Proc. Royal Soc. London B 270 (Suppl 1): S8–S11. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2003.0014. PMC 1698035. PMID 12952622.

- Spring Predictability and Leap-Frog Migration Alerstam et al Ornis Scandinavica (Scandinavian Journal of Ornithology) Vol. 11, No. 3 (Dec., 1980), pp. 196-200 (5 pages) Published By: Wiley

- Reverse migration (birds) - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia, • #Vinicombe, Keith; David Cottridge (1996).

- The Cornell Lab of Ornithology All About Birds : Migration

- US Fish and Wildlife Service

- See https://ebird.org/news/flywaypaper/

- F. A. La Sorte, D. Fink, W. M. Hochachka, A. Farnsworth, A. D. Rodewald, K. V. Rosenberg, B. L. Sullivan, D. W. Winkler, C. Wood, and Kelling, S. (2014). The role of atmospheric conditions in the seasonal dynamics of North American migration flyways. Journal of Biogeography 41(9): 1685-1696. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.12328

- Midway's albatross population stable, Honolulu Advertiser, December 27, 2016

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Midway_Atoll Wikipedia Midway Atoll, Environment

- https://friendsofmidway.org/explore/wildlife-plants/birds/migratory-birds/ Friends of Midway Atoll, migratory species

- https://migration.pwnet.org/pdf/Flyways.pdf

- https://www.fws.gov/refuge/hanalei Hanalei National Wildlife Refuge

- https://www.eaaflyway.net/task-force-on-illegal-hunting-taking-and-trade-of-migratory-waterbirds/

- H. Biebach et al. Strategies of Trans-Sahara Migrants https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-642-74542-3_23

- https://www.audubon.org/news/more-1000-birds-collided-single-chicago-building-one-night

- https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/apr/07/how-many-birds-killed-by-skyscrapers-american-cities-report

- https://www.fws.gov/story/threats-birds-collisions-road-vehicles

- https://www.wetlandtrust.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Ramsar_in_the_Pacific_V_Jungblut.pdf

- https://rsis.ramsar.org/ris/244

- https://www.birdscanada.org/conserve-birds/fraser-river-estuary

- https://www.birdscanada.org/new-paper-underlines-importance-of-bcs-fraser-delta-to-birds

- https://whsrn.org/whsrn_sites/copper-river-delta/

- https://whsrn.org/linking-sites/pacific/copper-river-delta/

- https://www.adfg.alaska.gov/static/lands/protectedareas/_land_status_maps/copperriverdeltals.pdf

- R. A. Stillman et al,Predicting impacts of food competition, climate, and disturbance on a long-distance migratory herbivore March 2021 https://esajournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ecs2.3405

- Makereta Komai, The Wandering Tattler – a migratory sea-bird of importance to Fiji, December 2020 https://pasifika.news/2020/12/the-wandering-tattler-a-migratory-sea-bird-of-importance-to-fiji/

- D. W. Stinson et al, Pacific Science 1997, vol.51, no.3: 314-327, Migrant Land Birds and Water Birds in the Mariana Islands! https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/5095274.pdf

- Alexandra Mae Jones, Bird reportedly flies 12,000 km non-stop from Alaska to New Zealand, breaking record, October 2020, https://www.ctvnews.ca/sci-tech/bird-reportedly-flies-12-000-km-non-stop-from-alaska-to-new-zealand-breaking-record-1.5147565?cache=yes%3Fclipid%3D104056

- https://www.doc.govt.nz/nature/pests-and-threats/animal-pests/possums/

- https://www.doc.govt.nz/news/media-releases/2010/possums-eat-kea/

- David R. Towns et al, November 2004 Have the Harmful Effects of_Introduced Rats on Islands been Exaggerated? https://www.researchgate.net/publication/225530166

- Gerard Gray et al, MONTSERRAT CENTRE HILLS FERAL LIVESTOCK ACTION PLAN, https://www.nature.com/articles/ncomms2380

- Félix M. Medina et al, A global review of the impacts of invasive cats on island endangered vertebrates, June 2011, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02464.x

- Scott R. Loss et al, The impact of free-ranging domestic cats on wildlife of the United States, December 2013, https://www.nature.com/articles/ncomms2380

- Theunis Piersma et al, The Pacific as the world’s greatest theater of bird migration: Extreme flights spark questions about physiological capabilities, behavior, and the evolution of migratory pathways, Ornithology, Volume 139, Issue 2, 8 April 2022, https://academic.oup.com/auk/article/139/2/ukab086/6523130?login=false

Recommended Citation

- BirdForum Opus contributors. (2024) Migration. In: BirdForum, the forum for wild birds and birding. Retrieved 29 April 2024 from https://www.birdforum.net/opus/Migration